Introduction

Multi Modal Large Language Models (MMLLMs) are one of most exciting emerging technologies in the field of AI. They fuse diverse modalities to perform complex tasks. They harness power of Large Language Models (LLMs) to perform multi-modal tasks [1]. Example for multi model tasks include but are not limited to:

- Image Captioning -> Uses images and texts

- Visual Question Answering (VQA) -> Uses images and texts

- Visual Dialog -> Uses images and texts

- Emotion Recognition in Video Calls -> Uses audio, video and text

- Counting objects (as we will discuss in this essay), performing geometric reasoning

As listed above, the modalities MMLLMs work with are not necessarily limited to image and text, MMLLMs can work with audio, video and other modalities as well. In this short technical demonstration, we will consider LLaVA – a cutting edge MMLLM that works with images and texts. Training and deploying MMLLMs is challenging and currently a heated area of research since combining foundational models that are pretrained on their respective modalities is not a trivial [1].

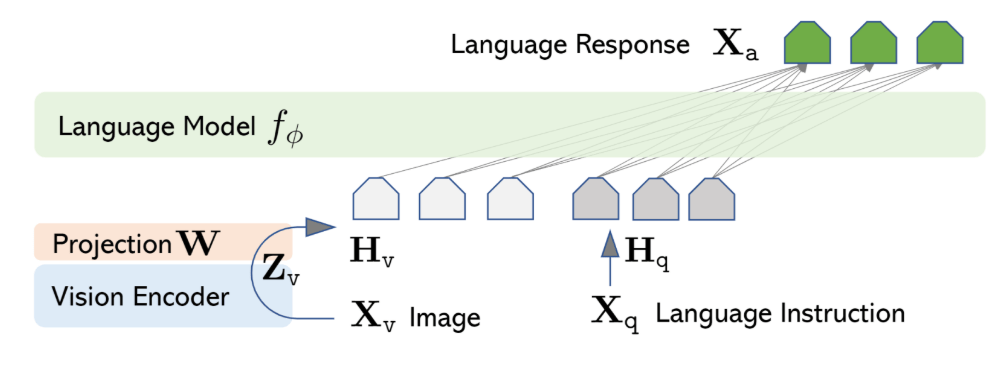

Large Language and Vision Assistant (LLaVA) is a cutting edge MMLLM that was introduced in 2023 by Liu et al. and is powered by visual instruction tuning technique to achieve ChatGPT-level conversation capabilities [2]. LLaVA works with text and image modalities and is powered by a pretrained large language model (LLM) and a visual encoder (CLIP ViT – L/14) . A high-level architecture can be seen in figure 1. LLaVA consists of a vision encoder that encodes images, multimodal projector that projects these image encodings to the same shared space as the text embeddings of the instruction and finally a LLM (Vicuna) that concatenates projected and text embeddings to respond according to the image and instruction provided by the user.

What is Instruction Tuning and how it helps LLaVA to perform better in multi modal tasks?

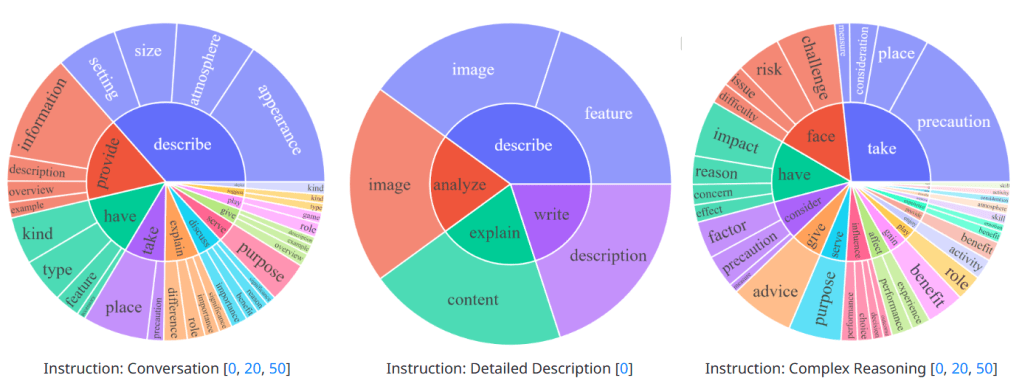

Instruction Tuning is a method that originated from the NLP community and is often used to finetune Large Language Models (LLMs) so they better align with desired behaviour for the users. In contrast to the pretraining phase that requires millions of samples and expensive training routines, instruction tuning can be performed with relatively small amount of annotated data. A desirable performance can be achieved using only 10 thousand human annotated conversations [2]. Most well-known example is InstructGPT that was obtained after applying instruction tuning to GPT-3. The tuned GPT-3 demonstrated less toxicity in its responses and performed better in tasks outside ones that were shown in the training phase [3]. This idea is borrowed to tune LLaVA for improving ability of the model to follow multi modal instructions. One of the key challenges the developers of LLaVA cited was finding an extensive multimodal conversation training data for visual instruction tuning. Creating required amount of multimodal conversations is both time consuming and resource intensive. To mitigate this issue the authors came up with a novel pipeline for generation multimodal instruction following data. The resulting model establishes new benchmark performance on ScienceQA through fine-tuning and shows outstanding visual dialogue skills when adapted using multimodal chat training data [4]. The distribution of the topics for the multi modal conversation training data that used in visual instruction tuning is shown below in figure 2.

Besides visual instruction tuning, another training procedure was performed. This procedure aims to achieve better alignment in images and their corresponding captions. To achieve this alignment, 595 thousand image-caption pairs (from CC3M dataset) were used and during this alignment procedure only the projector module’s weights were updated [2].

The Object Counting Task and Finetuning MMLLMs for Downstream Tasks

Humans have an innate evolutionary ability to estimate number of objects in a given scene without explicitly counting each object in the scene. Such an ability is called numerosity sense in psychology. Numerosity sense is present in children and in many other species hinting that the ability is part of standard evolutionary development [5]. It is a fascinating experiment to test numerosity sense of current MMLLMs to see how they measure up against humans. In this essay for terminological simplicity we will call numerosity sense as object counting task and we will test solely performance of LLaVA.

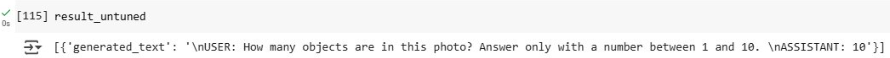

A downstream task is a task that utilizes the learned features and representations formed during the pre-training phase of an AI model for a specific real-world application. Popular examples include medical diagnosis, sentiment analysis and instance segmentation. In our case the downstream task is counting objects in an image. Before brain-storming on how to improve the object counting tasks we ask the untuned LLaVA to count objects to see how it performs without any tuning. We input the image below and ask LLaVA to count the object by the prompt.

The answer of LLaVA unfortunately isn’t entirely correct. This highlights the fact that LLaVA needs custom finetuning for downstream task of object counting. Before diving into nuts and bolts of the finetuning procedure let’s review architecture of LLaVA one more time.

LLaVA Architecture, Multimodal Fusion Techniques and the Multimodal Projector

MMLLMs revolutionize the field by using multiple modalities at the same time to reason and generate appropriate answers given the prompt, the image and previous answers it generated. In general, MMLLMs consist of a pretrained modality encoder, a pretrained LLM and a modality interface that bridges these modalities. A helpful analogy can be made by thinking these modality encoders as eyes/ears and the LLM as the brain that processes all of the received information from the encoders to come up with an answer [6]. Fusion techniques are used to meaningfully integrate the encoded information from the modality encoders. Fusion techniques can be categorized into 2 main subclasses: deep fusion and shallow fusion. In deep fusion, for each layer of the LLM there a new cross-attention mechanism is introduced so the modalities mix with each other at each layer of LLM. On the other hand, in shallow fusion a multi layer perceptron (MLP) is used to map encoded modalities into a shared space. All of mapped encodings are concatenated and fed to the LLM to get an answer that is conditioned on these modalities [7].

As a MMLLM, LLaVA uses shallow fusion and works with 2 modalities: image and text. As the diagram in Figure 1 suggests, the image is encoded by the image encoder (CLIP ViT-L/14) that functions as ‘eyes’ and is projected to the shared space by the projector MLP that consists of 2 linear transformations and a non-linear GeLU activation between these transformation. This projector acts as a bridge between the eyes (visual encoder) and the brain (LLM) [6].

Our Experiment: Finetuning LLaVA for Better Object Counting Performance

Experiment Set-up, the Dataset and Base Performance

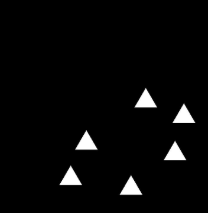

The dataset (based on the CCNL Dataset – Computational Cognitive Neuroscience Lab, University of Padova) consists of 3000 720×720 RGB images, 500 images for each unique category. For each category there are 10 numerosity categories: 50 images for each number of objects from 1 to 10. The images do not contain any background scenes, or overlapping objects, as a result counting number of objects in the image is a relatively straightforward task for humans. Some samples from the described dataset are shown below in figure 3:

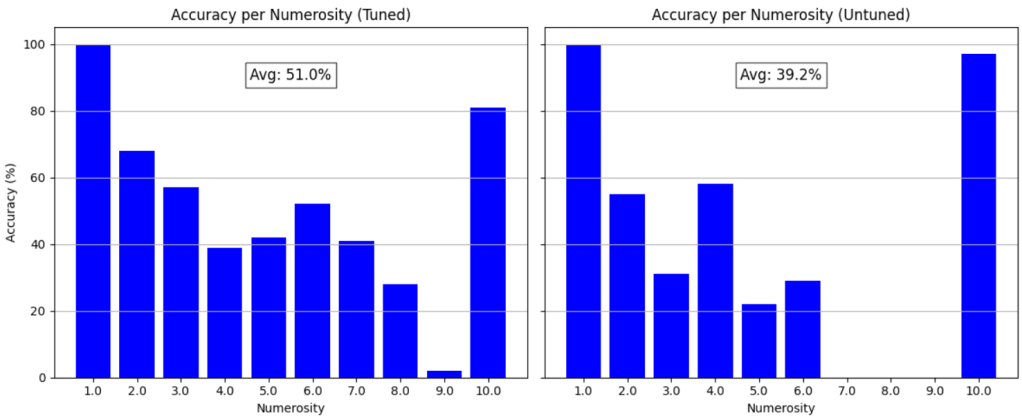

What will be the performance LLaVA in counting objects in the described dataset? To reliably compare the performance of tuned and untuned model without running into the risk of getting overly optimistic results due to overfitting we have split the dataset by categories into a training and validation set. The object categories in the training set include: apples, people and squares and the categories in the test set are: butterflies and triangles. For each image in the test set we asked LLaVA: ‘How many objects are in this photo? Answer please with a number between 1 and 10.’ We specifically asked LLaVA to answer us only with numbers, in the other case some answers include vague statements like ‘a few’, ‘a lot’. The accuracy per ground truth object count for the test set is shown in the graph below (untuned) and is 39.2%.

The overall object counting accuracy is just below 40 percent and accuracy tends to be much better for lower number of objects. This makes sense because counting objects reliably becomes a harder tasks as number of objects to be counted increase – the same phenomenon is observed also in humans. Now lets deep dive into the finetuning pipeline.

Finetuning considerations and Parameter Efficient Fine Tuning (PEFT)

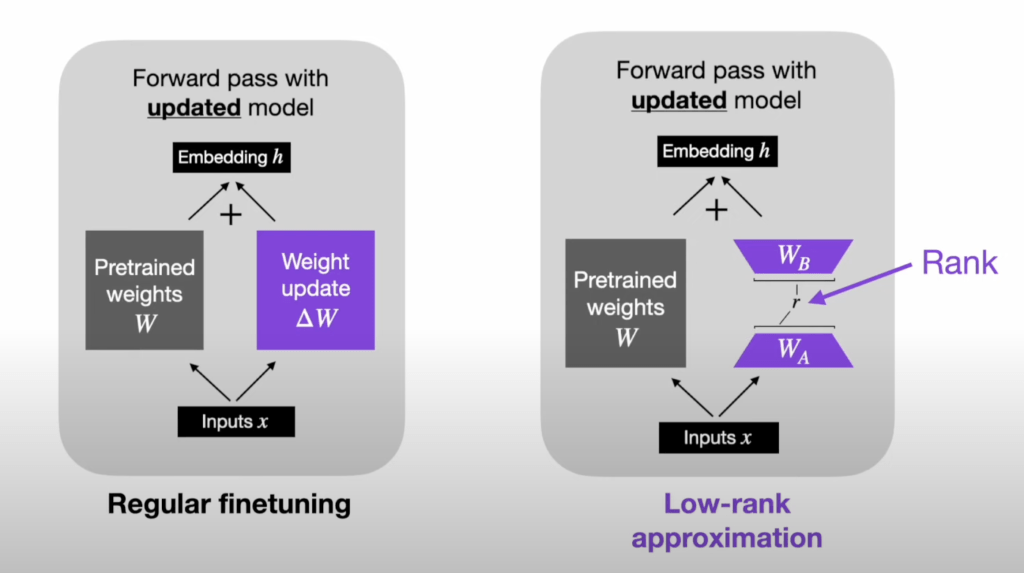

Most MMLLMs contain millions and even billions of parameters. As a result, finetuning them requires updating and storing billions of parameters which is very computationally expensive and carries a risk of overfitting (especially if the finetuning data is limited). To resolve this issue, researchers have developed Parameter Efficient Fine Tuning (PEFT) that involves adjusting only a smaller portion of all parameters. We use a type of PEFT – Low Rank Adaptation (LoRA) that involves injecting lightweight LoRA modules to specified layers that update parameters only in low-rank matrix increments [8]. An illustration summarizing how parameter updating works in LoRA is shown below in figure 5.

A critical hyperparameter in LoRA is rank of the updates (denoted with r). Lower values of r correspond to simpler updates, requiring even lower amount of compute and memory. Selecting r that is too low can cause underfitting thus it is best to treat the selection value of r as a trade-off between speed and capacity. r=8 works for most standard cases and it worked well for our task. In future works, we might explore different values of r.

Results and Experiment Discussion

As seen in figure 4, finetuning with PEFT improved overall object counting accuracy from 39.2% to 51.0%. Most importantly it ‘unblinded’ LLaVA for object counts larger than 6. In the untuned version, LLaVA just defaulted to predicting 10 or predicted a very small number when it encountered more than 6 objects. Fine-tuning allowed the model to output reasonable predictions for large numbers.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this short technical essay, we talked about Multi Modal Large Language Models, LLaVA and how capable are they in counting object in simple settings. We explored how one can improve performance of MMLLMs on downstream tasks without needing to allocate tens gigabytes of memory and days of training thanks to PEFT and showcased an intuitive example on how to improve the downstream task of counting objects using LoRA – a subtype of PEFT. Future discussions could include exploring other downstream tasks and considering more sophisticated tuning pipelines.

References

[1] Zhang, D., Yu, Y., Dong, J., Li, C., Su, D., Chu, C., & Yu, D. (2024). MM-LLMs: Recent Advances in Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.15470. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.15470

[2] Liu, H., Li, C., Wu, Q., & Lee, Y. J. (2023). Visual Instruction Tuning. University of Wisconsin–Madison, Microsoft Research, Columbia University. Available at: https://llava-vl.github.io

[3] Shu, M., Wang, J., Zhu, C., Geiping, J., Xiao, C., & Goldstein, T. (2024). On the Exploitability of Instruction Tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06409. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.06409

[4] Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., Almeida, D., Wainwright, C. L., Mishkin, P., Zhang, C., Agarwal, S., Slama, K., Ray, A., Schulman, J., Hilton, J., Kelton, F., Miller, L., Simens, M., Askell, A., Welinder, P., Christiano, P., Leike, J., & Lowe, R. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.02155. https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155

[5] Zorzi, M. & Testolin, A. (2018). An emergentist perspective on the origin of number sense. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1740), 20170043.

[6] Yin, S., Fu, C., Zhao, S., Li, K., Sun, X., Xu, T., & Chen, E. (2023). A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.13549

[8] Yin, S., Fu, C., Zhao, S., Li, K., Sun, X., Xu, T., & Chen, E. (2023). A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.13549. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.13549